Introduction

On April 5, 1815, as the sun was about to set and twilight was approaching, a massive explosion shook the island of Java in Indonesia, then under British control. Fearing an enemy attack, military vessels were dispatched from Java as well as Makassar on Sulawesi Island, about 800 km northeast of Java. Strangely, these vessels failed to find any threats lurking in the area. The following morning, however, ash was observed raining in parts of Java, indicating that the explosion could be attributed to a volcanic eruption. But this was no ordinary eruption. This was the beginning of a cataclysm that would not only impact Java or Indonesia but the entire world for months to come.

Reason for the eruption

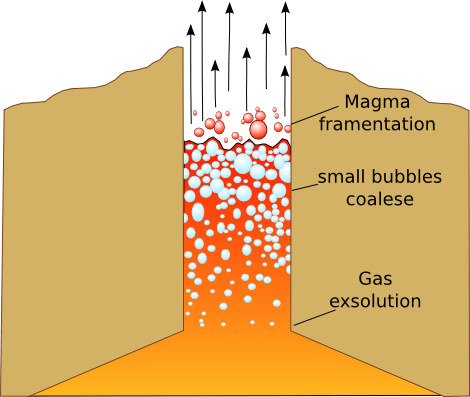

Unbeknownst to many, the Mt. Tambora volcano had been showing signs of activity since 1812, having spent centuries in dormancy. During this period, the magma in the volcano’s magma chamber cooled and crystallized. The relatively low temperatures in the magma chamber caused a process called exsolution to occur. During this process, volatile compounds like water and gases are separated from the magma. These volatile compounds then formed a separate gas phase in form of bubbles within the magma. This made the magma less dense, hence driving it up the main vent of the volcano. Moreover exsolved gases led to a gradual increase in pressure and temperature inside the magma chamber. All these factors eventually triggered an eruption accompanied by a humongous explosion, emitting tonnes of magma, ash and gases.

How the disaster unfolded

On April 5, 1815, Mt. Tambora finally erupted with an explosion heard more than 1,000 km away on the island of Java. Although this initial eruption was not immensely powerful, the one which followed was catastrophic. 5 days later on April 10, Mt. Tambora erupted again, with biblical proportions. Three separate plumes of ash and gases merged into a single colossal plume, eventually rising to around 43 km into the atmosphere, enveloping the sky in thick black smoke and blocking the sun for days. Over 100 km³ of volcanic material was ejected during this eruption, arguably the largest volcanic eruption in recorded human history. The enormity of this disaster can be understood by the fact that the mountain’s height reduced by over 1500 metres (Approx. 5000 ft) after the eruption. Initial pyroclastic flows (Fast-moving currents of volcanic material that flow along the ground from the volcano) completely wiped out the village of Tambora, situated on the slopes of the mountain and wreaked havoc in the nearby towns of Sanggar and Bima on the Island of Sumbawa. Tsunamis measuring as high as 4 meters were observed off Sulawesi and Java coasts. This was due to the sheer mass and momentum with which the pyroclastic flows hit the sea, displacing enormous volumes of seawater. An estimated 11,000-12,000 people were killed as a direct impact of this eruption and the following tsunamis.

The resulting ashfall from the eruption deposited a layer of ash at least 20 cm thick on the nearby islands of Bali, Lombok, and parts of Java. Moreover, around 500,000 km² of the area surrounding the volcano was covered by at least a 1 cm thick layer of ash. As a result of the ashfall and pumice rocks from the eruption, agriculture in Indonesia was severely impacted. Giant pumice rocks falling from the volcano destroyed existing crops, while ashfall caused soil fertility to reduce drastically. This led to widespread famine across the archipelago, causing a further 40,000-50,000 deaths.

Global Impact

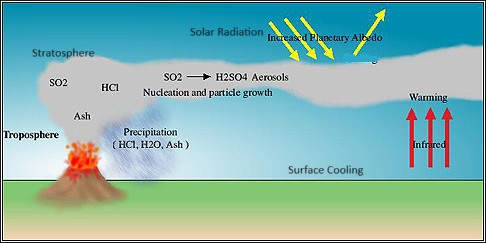

In addition to the monstrous ash plumes and gases like hydrogen chloride (HCl) and carbon dioxide, Mt. Tambora also emitted about 60 Tg of sulphur dioxide (SO₂) into the atmosphere (1 Tg = 10⁹ kg). SO₂ interacted with water vapor in the atmosphere to form sulphate aerosols (fine liquid particles suspended in the air), spreading worldwide due to winds. These sulphate aerosols persisted in the atmosphere for a few years, forming a veil around the planet. These aerosols caused two phenomena to occur as shown in figure 5:

- They scattered and reflected a significant portion of the incoming solar radiation (planetary albedo increased), hence preventing majority of it from reaching Earth’s surface.

- Earth’s surface emits radiation in the form of infrared rays into space, which maintains the temperature balance on the surface. The sulphate aerosols absorbed an immense amount of this radiation warming the upper atmosphere (stratosphere).

These phenomena led to the average global surface temperature plummeting by approximately 2˚C, resulting in frosty conditions throughout the year, particularly in 1816 in parts of Europe and North America. Due to unusually low temperatures, crops failed, leading to major food shortages and famine across the Northern Hemisphere. The situation in Ireland was particularly terrible due to the occurrence of a typhus epidemic around this period that claimed the lives of over 40,000 people.

Moreover, weather patterns altered significantly, leading to unseasonal rains and dry spells in India and China. Just like in Europe and North America, agriculture took a major hit. The province of Yunnan in China endured a three-year-long famine, while altered weather patterns led to changes in microbial ecology around the Bay of Bengal, causing the cholera bacterium to mutate. This led to a massive cholera epidemic in India, which was exacerbated by the food shortages. Due to freezing conditions persisting throughout the year, 1816 was termed as the ‘Year without a summer’.

Final words

It isn’t easy to ascertain the number of people affected directly or indirectly by the 1815 Tambora eruption and its aftereffects globally. Conservative estimates suggest a death toll of about 150,000-200,000, while millions faced hardships due to the resulting global cooling, floods, and droughts. This event had a remarkable impact on the global climate as well as the livelihoods of people around the world. It also shows how vulnerable we as a society are to the wrath of Mother Nature and begs the question: what would be the impact on our modern society if an eruption of a similar scale happened now?

References

- https://www.chemistryworld.com/features/sulfate-aerosols-and-the-summer-that-wasnt/1010160.article

- https://www.science.smith.edu/climatelit/the-eruption-of-mount-tambora-1815-1818/

- https://slate.com/technology/2014/04/tambora-eruption-caused-the-year-without-a-summer-cholera-opium-famine-and-arctic-exploration.html

- https://blogs.egu.eu/network/volcanicdegassing/2015/04/03/the-great-eruption-of-tambora-april-1815/

- https://www.wired.com/2015/04/tambora-1815-just-big-eruption/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9985606/

- https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/bams/77/9/1520-0477_1996_077_2077_slaywa_2_0_co_2.xml

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1191/0309133303pp379ra

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/1816-the-year-without-summer-excerpt/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377027314002601

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/037702738690079X?via%3Dihub

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/geology/article-abstract/12/11/659/188320/Volcanological-study-of-the-great-Tambora-eruption?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- https://hilo.hawaii.edu/campuscenter/hohonu/volumes/documents/Vol05x07ClimaticEffectsof1815EruptionofTambora.pdf

- https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/Aerosols/page3.php

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.224.4654.1191

- https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/71/1/012007/pdf

![Create a logo for a science-focused website [that embodies innovation] [and curiosity] [while exuding a modern and sleek aesthetic] that reflects a passion for scientific exploration. [It should integrate scientific elements] [and incorporate a sense of discovery].](https://scie99.blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/img-hxn9yfw6zqxcvavcolisqsxq.png)

Leave a reply to Aryak Save Cancel reply